What is Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome and How do I Deal With It?

This entry was posted in Addiction Recovery and tagged how do I deal with post acute withdrawal syndrome, post acute withdrawal syndrome, what is post acute withdrawal syndrome on August 07, 2020 by Justin Baksh, MS, LMHC, MCAP, Chief Clinical Officer.

Detoxing from drugs and alcohol is not pretty. The first week or two is “pure hell,” say some former users. Afterward, they breathe a sigh of relief, thinking, I’m past all of that. They go into treatment or back into the world and BAM! Post-acute withdrawal syndrome hits. A tidal wave of anxiety, fatigue and depression overwhelm them, along with a host of other bewildering physical and mental symptoms.

What is Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome?

In the addiction recovery process, post-acute withdrawal syndrome (PAWS) refers to a constellation of symptoms occurring after the acute phase of withdrawal, or a week or two after stopping use. Symptoms can last for months, even years.

PAWs has many other names, including:

- Protracted withdrawal

- Extended withdrawal

- Long-term withdrawal

- Late withdrawal

- Subacute withdrawal

- Post-use syndrome

- Protracted abstinence

- Sobriety-based symptoms

(Protracted Withdrawal | Publications and Digital Products, 2020)

Not everyone gets post-acute withdrawal syndrome, but many do. Estimates are that 90% of opioid users and 75% of amphetamine and alcohol users experience some form of PAWS. (Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome (PAWS) | Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior, 2020)

Prescription drugs such as benzodiazepines can also cause post-acute withdrawal syndrome. One study estimated that 30% of patients in general practice and 100% of those referred to a specialist were experiencing benzo withdrawal, for example.(Ashton, 1991)

The Symptoms: What Does PAWS Feels Like?

A wide-ranging list of symptoms for post-acute withdrawal syndrome has been put forward. Below are symptoms listed in the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA) protracted withdrawal bulletin, released in 2010:

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Irritability

- Fatigue

- Inability to focus/difficulty concentrating

- Sleep disturbances/insomnia

- Drug or alcohol cravings

- Short-term memory lapses

- Impaired decision-making ability

- Unexplained physical issues(especially pain)

- Decreased interest in sex

- Inability to feel pleasure (anhedonia)

- Impaired executive function(solving problems, e.g.)

Many former substance users paint a fuller picture of what it feels like to have PAWs, including some symptoms listed above… and some that are not:

- Lack of energy – Feeling too exhausted to shower, dragging themselves through the day, and collapsing on the couch after work is frequently described by PAWS sufferers. At the same tie they feel physically tired, they can still feel restless inside.

- Brain fog – Quite a few former users report lingering brain fog so thick that everyday tasks are difficult to complete.

- Brain zaps Brain zaps, or sudden jolts of electric shock passing through the brain, can happen randomly or after sudden head or eye movement. This feeling may co-occur with dizziness, nausea and tinnitus. (Brogaard, D., 2017)

- Memory issues –Struggling to find the right words or remember things long ago memorized make some PAWS sufferers question whether they are losing their minds.

- Derealization/Depersonalization– Former users can have a sense that nothing is real around them – they feel detached from their surroundings and the people in them. It may seem as if the world is distorted or that they are experiencing it through a veil, barrier, or glass wall.

- Disassociation – Reports of disassociation, or the feeling of being disconnected from your own thoughts and emotions, as well as an altered perception of time have been made.

- Quick to anger – Intense irritation in response to minor issues leading to angry outbursts are a problem for some PAWs sufferers. They report feeling as though their temper is on a hair-trigger.

- Malaise – Some say they feel a pervading unease or discomfort, no matter where they are or what they are doing. Sometimes these feelings are accompanied by a feeling of dread or impending doom.

- A hyper-focus on their symptoms– The physical and mental symptoms of post-acute withdrawal syndrome can occupy the mind day and night, along with a sense of despair that they will ever go away.

- Physical Symptoms – Muscle and joint aches have been reported, as well as feeling dizzy, shaky, jittery, fearful and panicky. Some also report twitching.

- Oversleeping – While insomnia is a common symptom of post-acute withdrawal syndrome, some former users feel compelled to oversleep – whether it’s 10, 12 or even more hours a night.

- Other anecdotal reports – Temporary blindness, numbness, tingling, dulled hearing and sense of smell have also been reported by former users.

The good news is that the symptoms seem to come and go in most. Former users describe bad days, where they are scraping the bottom, followed by feeling fine, as if they’ve got this, the next.

One interesting phenomenon is that more acute PAWS symptoms can occur at certain times – times that drinking or drug use occurred in past. Whether it’s happy hour, nights, weekends, holidays or vacations, their bodies are trained to expect a hit of their drug of choice when they occur. As a result, post-acute withdrawal syndrome sufferers may feel especially agitated and need to socially withdraw in order to cope whenever this occurs.

There is no need to fear PAWS, however. Former users can tell you that the worst of PAWS was better than active addiction.

And symptoms do get better with time. Many have reported complete remission by year two post-recovery.

As previously stated, not everyone in recovery experiences post-acute withdrawal syndrome. Those who do, don’t always experience it in the same way.

The Medical Community’s Take on PAWS

Imagine suffering some or debilitating symptoms that matching the descriptions of post-acute withdrawal syndrome above. You go to see your doctor, only to be told you shouldn’t be experiencing withdrawal any longer. It’s a frustrating experience to say the least.

The problem is that PAWS isn’t an official diagnosis (meaning it’s not listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5, or the DSM-5).

Although there are many commonalities, the symptoms are wide-ranging and somewhat unique to the individual.

After all, no two people typically abuse the same amounts of the same substances for the same length of time, nor do they have the same physical, mental and genetic makeup.

There are not many research studies on PAWS and there is no test for it. Medical treatment is limited to medications like Vivitrol or Suboxone, the latter of which can cause withdrawal itself if not tapered off of correctly.

That being said, many of us in the medical and psychological professions who regularly treat recovered patients have seen enough to recognize that the phenomena of post-acute withdrawal syndrome most definitely exists.

Because post-acute withdrawal syndrome is the reason many people relapse, it would be foolish not to try to address it.

What Causes Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome? The Healing Brain

One of the reasons PAWS can be so hard to pinpoint and treat is that it may simply be manifestation of the brain healing itself.

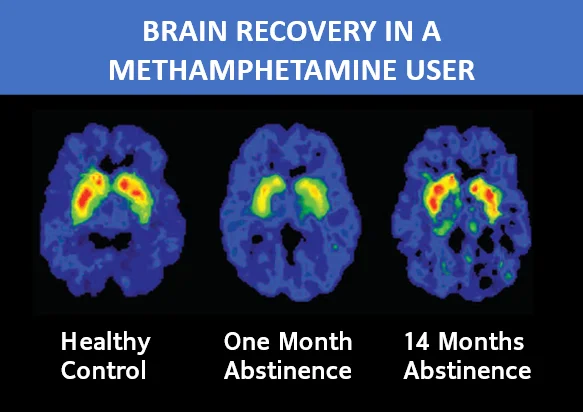

Brain activity scans have demonstrated the damage done by drugs and alcohol, and the brain’s return to near-normal functioning over time (meaning significant time, not one or two weeks). As you can see below, it took 14 months for a former meth user to obtain significant improvement in brain activity that is close to that of a healthy brain. (The Brain in Recovery – Recovery Research Institute, n.d.)

We already know that symptoms of withdrawal can be different for different substances. This is a direct result of the brain’s adaptation to the particular drug used.

Depressants such as alcohol or benzos have a calming effect, for example. The brain adjusts to these substances by making less of the chemicals that calm us. It’s a necessary change: The brain seeks homeostasis in order to function normally. (Davies, 2003)

This is also the mechanism behind tolerance. Over time, you need more and more of a drug or alcohol to achieve the same effect. The brain keeps adjusting at each level of drug or alcohol use, developing even more tolerance. It’s a vicious cycle – one that can end with overdose.

Now, when the alcohol or the benzos are suddenly taken away, the brain is still suppressing those calming chemicals. That’s why withdrawal from them often brings on the opposite state: Overstimulation, anxiety and agitation come on like a downhill freight train.

It takes time for the brain to recognize that the alcohol or the benzos aren’t coming back, and to adjust back to a more normal state. Thus, some withdrawal symptoms can persist for months after stopping use of the drug.

Opioids have a different effect. By binding to and activating the brain’s opioid receptors, they send dopamine – an estimated two to 10 times the “normal” amount – flooding into the brain. The brain adapts to this by lessening dopamine production and sensitivity.

When the opiates are taken away, former users are unable to experience pleasure in the normal way. Until the brain heals or compensates, that is.

This is just one of over a thousand impacts opioids have been found to have on the brain(Haydon, 2018).Withdrawal symptoms such as shaking, cramping, nausea and sweating are all a result of adaptations to a high level of opioids in the brain that become apparent after quitting the drug.

Opioids calm the locus coeruleus region of the brain that deals with stress. It is the main producer of norepinephrine which (along with adrenaline) increases blood pressure, heart rate and the flow of blood pumped by the heart as well as increasing blood sugar levels and breaking down fat to provide energy. The brain adapts to the high opioid level by cranking up the neurons there.

Once opioids are removed, the amped-up locus coeruleus produces horrible withdrawal symptoms such as anxiety, high blood pressure, profuse sweating, headaches and heart palpitations. (Haydon, 2018)

How Long Will Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome Last?

It can take six to 12 weeks to heal a hamstring pull or ankle sprain. For an ACL tear, it can take up to six months.

Why then do we expect the brain to heal from addiction after a week or two?

As complex and vital as our brain is (involved in everything we do, consciously and unconsciously, automatic and not), it can take a significantly longer amount of time to heal. Many PAWS sufferers are symptom-free by year two post-recovery.

You don’t have sit by and patiently wait, however. There are things you can do to feel better. Below are five ways to deal with post-acute withdrawal syndrome.

5 Ways to Deal With Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome

1. Do not use again

Sounds obvious, huh? Yes it is. Under the uncomfortable throes of PAWS symptoms, though, you may not stop and think about it. If you are tempted to relapse, it may help to know that this stops your brain healing progress in its tracks.

While it’s unclear how much drug or alcohol use, for how long, it takes to get back to the same brain-impaired state users were once in while in active addiction, why chance it?

View any drug or alcohol use as resetting the clock on brain healing and PAWS symptoms – just as would be day one again for your recovery in general.

2. Exercise

Exercise improves your brain health and helps speed healing. Studies show that it has also:

- Improves your ability to control your impulses

- Improves the blood flow in your brain

- Helps white matter integrity, an important factor in maintaining cognitive stability(Fjell et al., 2011) (a reduction in white matter integrity causes cognitive instability with symptoms including memory loss, lack of coordination, confused state, and more)

(“The Brain in Recovery – Recovery Research Institute”, n.d.)

How you get the exercise you need is up to you. It can start with just walking 20 or 30 minutes several times a week. As you gain strength, you can move on to weight training, running, swimming and more. The body’s response to exercise will amaze you. In a few months, you could be doing things you never thought you’d do.

3. Feed yourself well

The right food can help your brain recover. We can see this with traumatic brain injury sufferers. The following have been shown to aid in brain healing:

- Magnesium – pumpkin seeds, spinach, almonds, cashews, peanuts, black beans, edamame, dark chocolate, peanut butter

- Antioxidants – dark chocolate, pecans, blueberries, strawberries, raspberries, artichokes, kale, goji berries

- Omega-3 fatty acids – salmon, sardines, trout, soybeans, walnuts, kale spinach, soybeans, pumpkin seeds, flaxseed oil

- Choline – eggs

- Oleic Acid – avocados

- Berries – especially blueberries

- Zinc – red meat (moderate amounts), chickpeas, beans, lentils, squash seeds, soybeans

In addition, turmeric is a good source of curcumin which helps in the production of BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor). BDNF is vital to the process of creating new brain cells, or neurogenesis.

RELATED: Cooking and eating healthy after your rehab stay

How does organized nutrition help with addiction recovery?

4. Check out therapy

A 2019 study showed that an integrated behavorial and cognitive treatment approach helped control cravings, increase the brain’s response to natural rewards and help the brain heal from opioid-induced dysfunction after eight weeks. (Xu & LaBar, 2019)

Many treatment centers provide an outpatient option of one to three hours of counseling a week. This can be a budget-friendly option to get the help you need to get through post-acute withdrawal syndrome.

5. Look for progress, not perfection

Most of all, be kind to yourself. You are still recovering from the effects of your addiction. Look for progress over time. If you can think back weeks or months and see that at least it’s better than it was, you are headed in the right direction.

If you can’t remember how you felt yesterday, much less weeks ago, keep a journal of your symptoms and rate them on a 10-point scale.

Studies have shown that journaling:

- Boosts memory

- Increases mindfulness

- Improves communication skills

- Increases self-confidence

- Helps you sleep better

- Strengthens your immune system

- Boosts your IQ

- Helps wounds heal faster.

(Phelan, 2018)

If journaling just seems too much for you, text yourself a few lines about the day, rating symptoms and how you feel. It takes only seconds, and you still get the benefit of seeing how things have gotten better over time.

If you find that your post-acute withdrawal syndrome symptoms are not getting better, it’s time to see a doctor and/or therapist. There may be another issue. Physically, you could have nutritional deficiencies or an underlying health issue that needs to be addressed. Mentally, you may be experiencing anxiety or depression or another co-occurring disorder.

Remember that sometimes just getting through the day is enough when you are dealing with post-acute withdrawal syndrome. Do what you can, the best you can, when you can. Eventually you’ll feel better and get to everything you need to.

PAWS Prescription: Strive for Balance in All Things

The brain knows what it is doing when it seeks homeostasis. All of us need an equilibrium and a balanced approach to life.

Balance is key to our mental, spiritual and physical health.

Achieving the right balance in your life will not only help you to cope with the symptoms of post-acute withdrawal syndrome, but continue your recovery journey for a lifetime.

RELATED: Do you ever get over addiction?

Do you have an addictive personality? Take the quiz

Find out what it means to have an addictive personality

Former drug addict shares his story

Mother of a drug addict shares her story

Sources

Ashton, H. (1991). Protracted withdrawal syndromes from benzodiazepines. Journal Of Substance Abuse Treatment, 8(1-2), 19-28. doi.org.

The Brain in Recovery – Recovery Research Institute. Recovery Answers. Retrieved 7 August 2020, from recoveryanswers.org.

Brogaard D.M.Sci., Ph.D., B. (2020). What Causes Brain Zaps?. Psychology Today. Retrieved 7 August 2020, from psychologytoday.com.

Davies M. (2003). The role of GABAA receptors in mediating the effects of alcohol in the central nervous system. Journal of psychiatry & neuroscience : JPN, 28(4), 263–274.

Fjell, A., Westlye, L., Amlien, I., & Walhovd, K. (2011). Reduced White Matter Integrity Is Related to Cognitive Instability. Journal Of Neuroscience, 31(49), 18060-18072. doi.org.

Haydon, I. (2018). How opioids reshape your brain, and what scientists are learning about addiction. Medicalxpress.com. Retrieved 7 August 2020, from medicalxpress.com

Phelan, H. (2018). What’s All This About Journaling?. Nytimes.com. Retrieved 7 August 2020, from nytimes.com.

Post-Acute Withdrawal Syndrome (PAWS) | Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior. Semel.ucla.edu. (2020).Retrieved 7 August 2020, from semel.ucla.edu.

Protracted Withdrawal | Publications and Digital Products. Store.samhsa.gov. (2020). Retrieved 7 August 2020, from store.samhsa.gov.

Xu, B., & LaBar, K. (2019). Advances in understanding addiction treatment and recovery. Science Advances, 5(10), eaaz6596. doi.org.